Over 70% of large IT projects fail. Conventional remedies promise greater predictability and control but only marginally improve team engagement, collaboration, and innovation. Is it possible to trade predictability and control for better results?

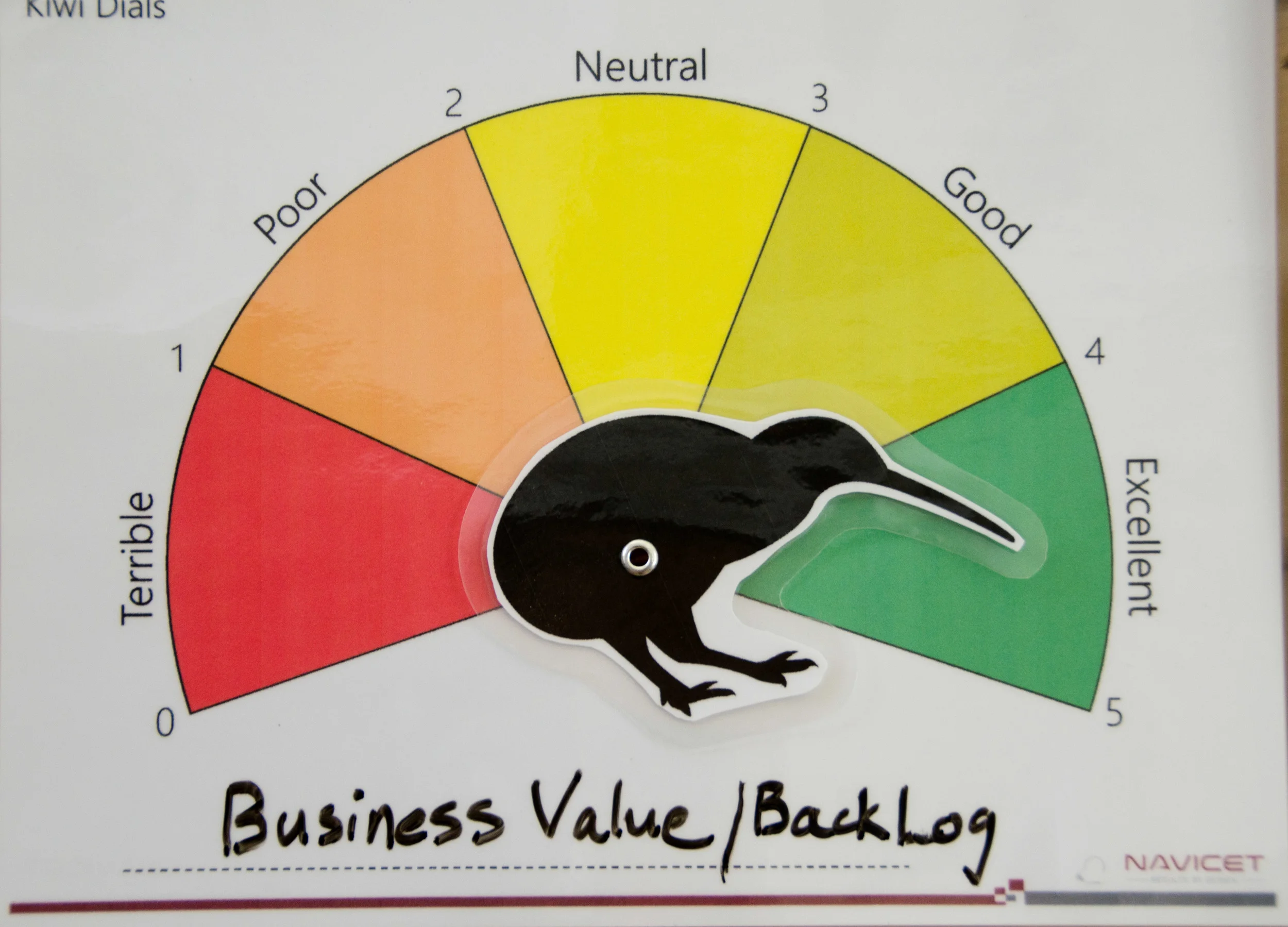

Here's a simple idea. Try using the same sensibilities you use to calculate story points for user stories for estimating business value.

What really counts for IT organizations? In most cases, the business struggles to get the most value from IT. They do their best to develop requirements, road maps and strong relationships, but still, they struggle with missed expectations.

Last week, I was talking with a group of super-smart architects when the topic of design came up. As you might expect, this happens pretty frequently for me. But this time, I was struck by how different our ideas were about the nature of design.

Most dictionaries offer mundane, concrete definitions for design, emphasizing either the creation of a specification or the planning of something to be built. In some cases, they touch on aesthetics, but only with some unease. Wikipedia, on the other hand, offers a scholarly analysis of different types of design and the intended purpose of each. It's a pretty tough read if you ask me. John Maeda, author of "The Laws of Simplicity", shares his thoughts on the topic on his blog. This is a pretty good read for the initiated with lots of insight and implications, but it feels like most of the talk is about design, how to recognize good design or the role of simplicity in design, for example, rather than an attempt to define it.

At Navicet, here's how we think about it...

I spent most of my 13 years at Microsoft developing ways for IT teams to deliver business value more effectively.

It was a long road. It all started when I joined Microsoft Consulting Services in 2001. I was delighted to find myself a small fish in a big pond of smart, motivated fish on the cutting edge of technology. The biggest surprise, however, was that the systems and tools that supported our business processes didn’t do a very good job supporting the actual work we needed to accomplish. This seemed like an ironic problem for a big technology company like Microsoft to have, so I set off to find out how this could be...

Four weeks ago, I packed up my office at Microsoft for the last time. In the quiet calm of a clear calendar, I had a chance to survey the 13 years I spent at the company, looking for the most important tidbits that I’d take with me. I ended up posting them as parting thoughts for the coworkers I was leaving behind.

They turned out to be pretty popular, so I’m sharing them here again...

Personas and user scenarios play a big role in Design for Business Value. When we first introduce the methodology, one common question we hear is, “My project doesn’t have any users, so will this still work for us?”

We were puzzled as to what type of project won’t have some impact on users, so we dug a little deeper...

Take the time to explore, to test your work, to learn and iterate, then test again. Take the time to learn more about who will use the product of your work, about their goals, desires, frustrations and obstacles. It takes time to learn how to do this well, to execute the work and incorporate it into the rhythm and governance of the project...

Collaboration is inconvenient. It takes time to share ideas, then more time to listen to ideas that other people have, and even more time to try and figure out which idea is best. It’s even harder when we have a big personal investment in our idea, or the other ideas might cause trouble for us.

Early in his career, Roger Martin, former Dean of the Rotman School of Management, was helping to facilitate tense negotiations between mine owners and local unions on whether to close a historic copper mine in upper Michigan...

Let’s say you are a manager. One of your many tasks is to decide how best to spend a million dollars. Maybe a morale event to Hawaii for your team? That would be fun. Or maybe approve that operations project to streamline your company’s billing process. That sounds like it should result in a better return than the Hawaii thing. But how will you know? How can you be certain that project delivers the promised benefits?

One option is to...

For most people, ambiguity leads to anxiety. Questions about whether a project stakeholder will be satisfied, whether the work can be completed within the expected time, or about whether an idea is technically feasible – all lead to fearful behavior on a project, both from managers as well as individual contributors. The usual response to this anxiety is to work as hard as possible to reduce the ambiguity of a project as quickly as possible. That means establishing detailed plans, specifications, requirements – anything to eliminate ambiguity.

Knowing exactly what work needs to be done by when feels reassuring. It makes it easier to manage expectations and spot problems based on deviations from the plan. But the benefits of certainty come with some costly tradeoffs...

9 people in a conference room, reviewing requirements. There’s debate, points made, counterpoints made. Slowly, with great effort, ideas develop and flit around each other, desperately seeking to converge. Homer is trying to track, trying to keep up. Marge is selling hard, sharing the urgency of her vision. Bart is doing his best to update the document to reflect what clarity he can glean from the discussion. Others disengage, waiting for a topic that concerns them more directly. Reading the document a few days later, none of it makes sense. Sound familiar?

We’ve seen teams make some odd decisions over the years, and the thing that we always end up puzzling over is, why? How come they made that decision?

Sometimes it seems like it’s just what they can agree on, even if no one’s happy. Underneath the surface, we observe, everyone seems to be striving for different objectives. Rallying around business value, the reason for the work in the first place, is one obvious way to bring diverse teams together...

This little phrase has been popping up all over lately, attributed to multiple sources. Here’s why it has such a powerful effect on how we approach IT work.

The most intuitive way to avoid mistakes is to plan carefully. Thinking about the big picture, ideally, means that every step you take moves you one step closer to the goal. And having a shared, common vision means that everyone can work independently and produce results that move the team forward. Result: less rework and less communication overhead. If complete, accurate, detailed plans don’t get you where you want to go, then, presumably, they aren’t complete, accurate or detailed enough.

Thinking about the big picture is pretty important, as far as it goes. The problem is that...

Okay, buckle your seatbelt for this one. It’s a simple idea that is essential for healthy design, innovation and producing high quality work, but it’s pretty counter-intuitive for most IT pros. Let’s start with the first part: “Start work as soon as possible,” or

How often have you heard, or maybe asked, this question, “When will the requirements be done and locked?” Or, “When will the research be finished?” Or, “When will spec be signed off?”

Most people like to ask these “When will the work be done” questions because we feel like the answer gives us a measure of progress. We know that when a certain category of work is complete, it adds to the road in our rear view mirror and less road remains ahead.

Too often, however, we find...

Greetings. I’m delighted that you’ve found your way here, since it means that you’ve read something, heard something, or had a conversation that inspired you, or got you wondering about a new idea.

We’ll make it as easy as we possibly can for you to grab a nugget here and there as your time and interest allow, or dig deep into a meaty topic that has particular application for you.

Delighted? Mystified? Tickled? Challenged? Let us know. We love the work we do and we think about it all the time. All of us at Navicet have a voracious appetite for insight and pragmatic approaches to hard problems. We’d love to hear your thoughts.

Take your time. We are glad you found us.